According to the Ancient Egyptian tradition, voiced by Manetho, Herodotos and the Ancient Egyptian kinglists, the 1st Dynasty started with the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt by the almost legendary king Menes. While the archaeological record does not mention Menes, this approximately coincides with the appearance of the first recognisable royal names in contemporary written sources.

King “Scorpion” is often assumed to have been either a predecessor or a rival of Narmer, but may, in fact, have been none other than Narmer himself!

The issue of the identification of Menes aside, the first king to be prominently present in the available source material is Horus Narmer. Two of his named predecessors, Horus Ka and Horus “Mouth” (or Iri-Hor) have been attested in Middle and Lower Egypt, but apparently not in the south of the country. While this may be due to a lack of sources, this could possibly indicate that their influence did not extend to the south of Egypt.

A king identified as “Scorpion” and known only through one ceremonial macehead is assumed by some to have been Narmer’s immediate predecessor or a rival king. It is, however, also possible that Narmer and “Scorpion” were, in fact, the same king identified through different dangerous animals.

While Narmer’s tomb was still rather modest, that of his predecessors suggest an increase in wealth. This is confirmed by the increase in source material from the 1st Dynasty. Such sources include seal impressions, wooden or ivory labels, inscriptions on stone vessels and so on. Of particular interest are seal impressions and labels that inform us not only of some events that took place, but also of the country’s administration.

In order to handle this administration, palaces were built and royal estates and domains were founded. The names of several high officials who were in charge of such estates have been attested. As the 1st Dynasty progresses, the titularies, often missing during the first kings, become more abundant, giving us some insight in the roles and responsibilities of Egypt’s early administrators.

Such was the prestige of these high officials, that they were buried in impressive tombs, the grandeur of which led many researchers to believe that these were the actual royal tombs!

A label dated to the reign of Horus Aha records a military campaign of this king against Ta-Seti, the land south of Egypt, Nubia. Rivalry and an economical interest in Nubia would remain a constant in Ancient Egypt’s foreign policy for thousands of years to come. To underline that rivalry, the early kings of the 1st Dynasty built a fortress on the island of Elephantine, near modern-day Aswan, on the southern border of their country. A noticeable decline in Nubian artefacts in the south of Egypt coincides with the building of this fortress.

That this fortress was built right outside a local temple, shows a very strong disregard of the ruling elite for the culture of the island’s inhabitants.

A similar display of absolute power is made in the simultaneous burial of some royal servants and even members of the ruling elite, along with the king, a practice that started with Horus Aha and was abandoned at the end of the 1st Dynasty.

Artefacts such as stone vessels coming from Syria-Palestina are witnesses to an intensive trade with that region. One label dated to the reign of Horus Den reports the first victory of this king in the “East”, perhaps as part of securing the trade routes with the Ancient Near East.

Den’s reign, which started with the regency of his mother, Merneith, marks several innovations, not in the least the introduction of the title nsw-bi.tj, usually translated as “King of Upper and Lower Egypt” and the Double Crown, both a reference to Egypt as the unity of two countries.

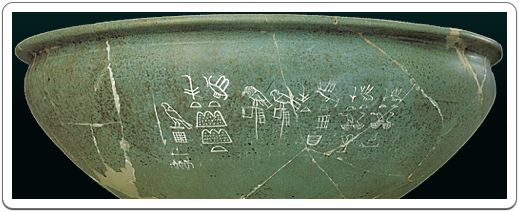

The order of succession of the last kings of the dynasty is attested on a palace vessel found underneath the Step Pyramid of Horus Netjerikhet at Saqqara that lists the Nebti Names of Den, Anedjib, Semerkhet and Qa’a. These Nebti Names correspond well with the last four kings in Manetho’s 1st Dynasty.

Stone vase listing the names of the last four kings of the 1st Dynasty.

Source: Tiradriti, Egyptian Treasures, p. 32.

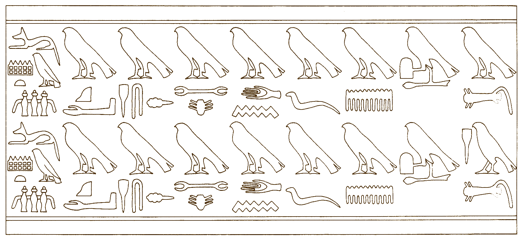

The impressions of a seal found at Umm el-Qa’ab provide the list of kings up to Horus Den. The list, alternating kings’ names with that of Khenamenti, the protector god of the royal necropolis, starts with Narmer and ends with Den and the Queen-Mother Merneith.

A similar seal, dated to the reign of Qa’a, lists all the kings from the 1st Dynasty in reverse chronological order, from Qa’a to Narmer. It is interesting to note that although Narmer’s predecessors were also buried at this necropolis, they are missing in both seals, either because their reigns had been forgotten or because neither Den nor Qa’a considered them part of their royal lineage. The omission of Merneith in the second seal is also interesting but would rather indicate that during Qa’a’s reign, Merneith’s regency was considered as part of her son’s rule and not as an independent rule. This corresponds with the list of succession provided by the king-lists and Manetho.

Seal impression listing the kings buried at Umm el-Qa’ab, listing, from left to right: Khentamentiu (the protector-god of the necropolis), Qa’a, Semerkhet, Anedjib, Den, Djet, Djer, Aha and Narmer.

Source: Dreyer, Ein Siegel der frühzeitlichen Köningsnekropole van Abydos, in MDAIK 43 (1986)

Although the division into dynasties was made by Manetho and is not reflected in kinglists like the Turin Canon, the fact that Horus Qa'a's immediate successors chose to be buried at Saqqara, near Memphis, rather than Umm el-Qa'ab, may be seen as a breach with the habits and traditions of the kings of the 1st Dynasty. With the move to Saqqara, the practice of retainer sacrifice started under Horus Aha, was also abandoned.

The mention of a Horus Ba and a Horus Seneferka in some rare inscriptions believed to date to this era hints at some upheaval during the reign of Qa’a or at the end of it. It is, however, not clear whether Horus Seneferka was another name used by Qa'a, or the name of an obscure king.

The name of Qa’a’s successor, Hotepsekhemwi, meaning “the two powerful ones are at peace”, is sometimes interpreted as an indication that this king reunited a divided country. That Hotepsekhemwi’s name has been found on seal impression in the tomb of Qa’a may indicate that Hotepsekhemwi took care of Qa’a’s burial, or that he had the tomb inspected and resealed after a period of turmoil.

Click on the thumbnails below to learn more about the kings of the 1st Dynasty.